Exploring A World of Culture, Oil and Golf with David Allard

1980 was one of the largest booms ever in the oil and gas business, and David Allard was in the right place at the right time. David just got out of college with a Geology degree and was lucky enough to get a job with only a BS degree and covered twenty plus countries over a twenty plus year period of exploration around the globe that comes with being a geologist in the oil field. Over his career, David has survived five major downturns. David chronicles 30 years of being a geologist in a book called A World of Culture, Oil and Golf which is journal of his life lessons, and business and cultural experiences. David said it’s key to the success for the business to engage the host country and follow the rules and create value for everyone involved.

—

Exploring A World of Culture, Oil and Golf with David Allard

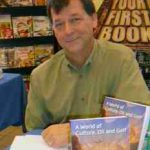

We’re fortunate to have David Allard. He is a chief geologist and author of A World of Culture, Oil and Golf. I went through the book and I would encourage you to go through. I think there’s no place on the planet that this guy hasn’t either landed on, been in or been over, or so highly traveled. Thanks so much for taking time.

Thank you, Bob. It’s my pleasure to be here.

Let’s start with the story that got you into the oil and gas business.

A World of Culture, Oil and Golf

A World of Culture, Oil and Golf

That’s fun because growing up I knew I was going to be an Earth Scientist from junior high during the sand experiments with little rivers. I grew up and went to college. In the first orientation day, I was going to be a forestry major. I met some professors and they said, “That would be a good thing if you’ve got a PhD, but then you probably wouldn’t get a job. Why don’t you be a geologist?” I changed right there and I’ve been a geologist ever since.

Where did you go to school?

Edinboro University of Pennsylvania.

Geologists in Pennsylvania in the oil field, I usually hear Colorado School of Mines, South Dakota or the Dakotas and elsewhere through Pennsylvania with the kind in mind but the Marcellus kind of brought that in.

Back in 1980 when I graduated, it was one of the largest booms ever in the oil and gas business. They needed a geologist and my professor said you can work anywhere. I went to California and I ended up with Sohio initially in San Francisco. I was lucky enough to get a job with only a BS degree. I call myself a Boom Baby, if you will.

You graduated in ’80s while the oilfield began puny not long after that.

I maybe not so proudly say I’ve survived five major downturns and the first one you’re speaking of about 1985, ’86. There was some disruption in the force of OPEC and Saudi, a commitment of the oil reserve and it just changed the world demand and we had our first downturn. We went from thinking we’re going to have $100 oil forever. A lot of business leaders bet the farm on that future income. Many of them went by the wayside in the ’80s because of it.

You went to San Francisco. Were you married at that time or when did you meet your bride?

I met my bride at Midland, Texas in the mid ’80s.

Thinking about folks who have different thoughts, what does a geologist do in the oil field?

Our job as geologists, the bottom line is we say, “Here’s where you drill to find more oil and gas production or reserves,” whatever the objective of your company model is.

You point the drilling rig?

Essentially, and we do that with a series of tools. Of course, we map the subsurface and try to identify structures are traps for the oil and gas. That technology’s evolved quite a bit. In recent years real improvement and success rate came from 3D seismic.

Does it follow along with the computer capability? I can remember there were a few companies that started out in that 3D graphic world way back then. Let’s talk about the book because I think most people have no idea about how much travel and exploration around the globe comes with being a geologist in the oil field. Going through the book, how many countries did you say you’ve been through?

The book covers twenty plus countries over a twenty plus year period. I personally visited 40 or more countries, but I focused on the business aspect of experiences in the book. My very first move was with a major oil company. I did several years in the US space with a variety of jobs, production, exploration. I joined the international group and within a couple of weeks I found myself in Turkey and riding up the mountains with a guy that spoke very little English and he had one cassette tape.

He said, “You like music?” He played Michael Jackson for five hours. I’ve got to the rig and the geologist who was relieving said, “That’d be a great thing for your journal.” It hit me from that point forward for the next twenty plus years and I kept a journal. I distilled that down to a readable novel format that is the book now. I feel like it’s a message to share my business experiences. A lot of the book talks about cultural experiences and reviews have picked up on that very in tuned with the local culture. It’s key to success for the business, to engage the host country and follow the rules and create value for everyone involved.

Be prepared to adapt to change.

I think about now when you hear Michael Jackson come on to the radio, does it take you back to your ride in Turkey?

On occasion, it does.

As you’re with me here domestically and then you get the word that you’re going to Turkey, you’re going to China, when you get that type of heads up, what’s your thought process when you’re going to a country?

As a geologist, the first thing we do is make maps and say, “Drill here,” but we have to understand the history of that geologic basin. We talk about how the rocks, sand, shale or whatever the target is, what are the risks of the oil business? We work that together with the engineers. We do a lot of homework on these subsurface, if you will. The surface is a whole other world.

Either there’s a surface risk, political, military, terrorism and just things like that that you have to consider. I was lucky enough to work for larger companies that had the resource to research the security risk above ground risk, political and fiscal risk well in advance. By the time we got there to drill wells, there had been a lot of homework. There would been a deal made and negotiated contract and that kind of thing so there are many aspects of it.

We were talking about that you’re a runner and you’re a golfer. I think about trying to stay in the running game when you’re out in some of these remote sites and yet you still ran.

I took a few jogs around the perimeter of our jungle of boats in Guatemala. I didn’t leave the perimeter in Chad, Central Africa. My very first trip to Turkey was when I took off into the mountains but that was my first trip and I didn’t understand the security as well as I do now.

You go to these foreign locations and people don’t have an idea of the duration of your time on the ground in those days. Talk a little bit about how long you were on ground and why that was done that way?

Typically, an international venture starts with the company deciding to enter that country and they’ve portrayed the chance for success, the geology, the potential reserves, whatever fiscal terms and political risks. You enter the country and you may win a license. That license may be a bid round sale with the government where you obligate to drill a couple of wells, shoots and seismic, hire some local labor, some engagement locally.

You may get a license and not drill the well for say a year or two as you digest the data and you make an exploration discovery, especially if it’s a remote away from facilities. It may be years of going back and drilling appraisal wells and then finally deciding to make that jump to a development, which is an incredible amount of money to move into an oil and gas business. The amount of years, investment and risk taken on by these companies long before they ever see the profit is part of the reason I wrote the book, to try to tell some stories and I was in different stages of development for different countries and different places.

For the folks up and down the front range of Colorado, we’ve seen seismic crews doing their work in the big wheeled vehicles, thumping around on the ground. In the jungles of Guatemala, Chad and other places, how far behind is it once you get the contract? Is seismic the next step? Once seismic is shot, is there a general timeframe between when they shoot seismic to when you elect to drill?

Yeah. Typically, it may take months or a year to acquire the seismic data. It depends how large of a footprint and what kind of seismic. If you’re remote working through a jungle that does not have roads, then that just add months and months. Typically, it may be a year cycle to permit, acquire, process and interpret the seismic before you ever have data that goes into the geology.

A World of Culture, Oil and Golf: The focus of geologists is the rocky outcrops or where there’s data with the hard data, rock data, oil and gas shows.

A World of Culture, Oil and Golf: The focus of geologists is the rocky outcrops or where there’s data with the hard data, rock data, oil and gas shows.

It may be a year or more to get to the point where the maps are becoming clear and then you present that to the leadership of your company, the decision makers and they may go, “Next year we’re going to drill.” There may be cycles of windows of opportunities to drill. For example, in Alaska you can only draw in the winter because it’s an onshore North Slope. There is some place to work in there but you can only drill in the winter because you want the ground frozen so you don’t damage the permafrost tundra layer.

You were on the receiving end of those budgetary decisions early in your career. Later in your career you were involved more about the decisions on budget, where to send and what to do?

That’s correct. Early in my career, I was the guy that went out to the well site and made sure that we’re capturing the rock samples, running logs to collect data and understand if we have a discovery well or not. Then later on, I moved into management at GM and my final position was the chief geologist. You see the budget, you see the strategy, and you’re working together as a leadership team to decide, “Do we want to take some more risk and go further in this country or do we want to stay in the US?”

You’ve seen a tremendous swing with the onset of horizontal drilling. Horizontal drilling and fracking is a labor intensive, investment intensive but at a lower risk. Once you’ve established a play that’s horizontally drilled, oil company leadership likes that because it’s repeatable. Generally, there’s more geology variation than people portrayed and we’re learning that. That changed the focus of a lot of companies. When I was in the international exploration game in the ’90s or early 2000s, that was a very popular target for companies for growth that we’re of decent size because there was marginally very little exploration in some prolific areas.

When you were working on the rig and you were looking at samples, I don’t think people understand very well that aren’t in the industry were those samples come from and how you got your hands on it.

As the drilling bit is going down through the Earth through hard rock into a basin that’s mature enough, deep enough and hot enough to generate oil and gas, you drill through a lot of layers and these rotary bits churn up tiny little samples that are about as big as your pinky fingernail or smaller. You’re looking under a microscope at these little chips or rock and you might have a trace of oil.

You’re also monitoring these rotary rig systems having contained a fluid system. There are fluids on the spinning drill bits and those fluids lift those cuttings up around the drilling to essentially spit out at the surface. People collect the samples, bring them in, the mud loggers, look at those, and we get that data. At the same time that fluid system has gas monitors all over it for safety reasons.

We look at that gas variation specifically what hydrocarbon contents are in it, and we see gas increases associated with productive oil and gas zone. These are the hardcore elements the rock, oil, and gas samples, the gas well drilling and the rate of penetration of the bit. If the bit hits some space in the rocket, it might drill faster. We call that a drilling break. After that, you’ll run wireline logs and those interpretations of density, resistivity, porosity and what saturation you think is in the rock, whether it’s water, gas or oil those are all key elements. That’s what the geologists bring. Then you marry that with the geophysical interpretation of seismic data.

The focus of geologists is the rock outcrops or where there’s well data with the hard data, rock data, oil and gas shows. The geophysics and the seismic strings that together to get a view of the whole basin if you spent the money to shoot seismic over the whole basin or a large area. Then you start seeing an image of the subsurface and we calibrate it with the rock data from the wells.

We then go on to make our maps of the joint effort and then we show the engineers. We have these traps. We think there’s this much oil and gas in place and the engineers typically take that and figure out the recovery system mechanism and the economics of the total project, not just a drilling a well. If you drill an exploration well, make a discovery and find this volume, is that going to be attractive economically?

I wanted to go through the detail because I think there’s a lot of confusion. People see a rig out there. They see a bunch of trucks around it and I don’t think they have any idea necessarily what goes on and how hard the work is in some of the places when you’re in a foreign country. It can be a multinational crew and living conditions can be interesting. In going from that, when you got the urging of one of your friends to write that down in your journal, you were thinking about writing this book, A World of Culture, Oil and Golf twenty plus years ago?

That’s correct.

Companies that are successful in international ventures put effort with the HR side to accommodate people and brief them what to expect.

When did you start writing this book?

I kept a journal for a number of years because I thought it was a good idea. As that volume started to grow, I thought this might be the content for a great book. I was lucky enough to travel a lot of business class, and I sat next to many very high powered executive types in various industries. We ended up talking about the concept, fiction, nonfiction, what should I focus on? I had a lot of years of evolving, but I finally decided to stop keeping a journal and start writing the book in 2010. I was working with a team and we were flying to Trinidad. We were going down there to look at a licensed round offered by the government, leases for sale.

We were evaluating those and whether the company was going to bid and decide to enter Trinidad or not. While we were flying over the Gulf of Mexico, I looked down and I said, “That’s Macondo.” If you don’t know in 2010, there was a well drilled and it blew out in the Gulf of Mexico called Macondo. BP was the operator that’s well-known publicly and spilled a lot of oil. It was disastrous for the entire industry because the government reacted harshly and constrained offshore drilling for a long time. A lot of people lost jobs while they figured out how to improve safety procedures and containment, which ended up being a good thing. There was a lot of involvement that way.

There I was flying at 35,000 feet. I looked down and I could see the rig and the drill ships around it. They were trying to drill relief wells to stop the flow of oil, which was still spilling into the Gulf of Mexico and I could see the sheen oil over the surface. I just thought, “I’m going to stop right now and write my book.” That was about 2010 and the book was published in November of 2016. I met a publisher and we found somebody to help me type up all the content. I eventually got a professional writer as a coauthor to change it from details of journal that nobody would care about into a flowing book that people would enjoy reading hopefully and so far, they have.

I think about the journey from all the travels and as you’re sitting out in the jungles of Guatemala, logging thoughts into your journal. I’ve got to imagine that your journals are rather interesting looking after all the trips and travels and locales. You still have all your journals?

We still have the original journals in a box somewhere for sure.

An insight what folks don’t know who haven’t looked in the book is the photos in there that you took along the way. Somewhere you were standing in some places that look sketchy.

Guatemala is a good one, which you brought up. We flew to Guatemala City in our own plane north towards the Tikal Mayan Ruins that people may know about, but it’s triple canopy jungle. We were making an exploration play for carbonate reservoirs, small structures over the northern parts of onshore Guatemala. That meant we flew in the small plane, about an hour, landed on a dirt strip, went down in trucks to a river, rode these longboats in another half hour up the river, got into another truck, and drove this location with a road that we carved into the jungle the company did. We were totally remote.

At that time, the leftist rebels were still fighting the government. We had a carved perimeter, barbwire security guards and everything. The rebels visited our location and they were heroes to the local people because they were fighting for their cause but that turned south, and the rebels took over the location while we were there. The regular army marched in 500 armies and they were patrolling the jungle after. The regular army were like Vietnam style there. I became friends with the army guys and they said, “While you’re sleeping tonight, we’re going to send this patrol out into the jungle looking for the rebels.” I said, “What am I doing here?”

As you were talking about planes, trains, automobiles and canoe, how did they get the equipment into the site?

The facilitators, engineers, planners, that’s whole other part of the business.

Were they afraid of the river or the barge?

I imagine they were. Yes. The rig parts from the major ports, they used large trucks and helicopters, whatever it took. I was in so many settings that I’d get to the rig and by the time the geologist gets there, there’s a series of trailers, there’s water supply, there’s a commissary and kitchen. It’s a little city run on generator because you may be so remote you’re away from power source. It’s just fascinating what the engineers can do to set those things up.

As you look back over your career and you’ve got a vast experience, what advice would you offer to geologists that are new or anyone who’s thinking about getting in the geology field knowing what you know now?

A World of Culture, Oil and Golf: The industry is cyclical, so be prepared for some up and down times.

A World of Culture, Oil and Golf: The industry is cyclical, so be prepared for some up and down times.

First of all, the industry is cyclical, so be prepared for some up and down times. It’s the five downturns I experienced so you have to have a stern stomach to understand that the company may be looking at reducing budgets and cutting costs by 50%, 80% during the downtimes. That means letting people go. Your job is to understand the business the best you can and learn how to create value.

The other thing is I tried to learn everything I could about every aspect of the business, but as a geologist you want to build some technical skills specifically. I learned petrophysics fault seal and some other things early on that moved me into the leadership roles that I had later. Of course, in the leadership roles of a geoscience manager and in those jobs, there are people skills that are common to all businesses.

I’d say as a geologist going into the business, be prepared to adapt to change. When you’re working internationally, understand the host country and the culture because they are invariably part of the team, the local people. I enjoyed all the opportunities to learn the different cultures and the different teammates I had around the world. It’s a big part of it. Especially third world countries, people would say, “Oil and gas, such a dirty business.”

The way I look at it is we work with the government and if we agree to do a deal, go in there, work together and try to establish some additional oil and gas reserve that ends up being successful, that creates jobs, an income and an increased investment into that country. Until we figure out a complete alternative to oil and gas, as far as energy generation of product, we’re stuck with it.

As you were talking that early in the career, you travelled unaccompanied. You packed up and you left with your gear and you came back with your gear. Compare and contrast that when you started traveling with your family. What was the first trip? Was it to China that you went with your family or Egypt?

Egypt. Early on I did a lot of international work at the well site as you could tell by my comments and then as I moved into the general teamwork and business work, it was a business trip. Those don’t necessarily pay bonus and you’re going anyway to a lot of business trips. It was very exciting, and I’d come home, tell stories, and bring little trinkets and stuff. One of my goals was if I’m going to continue in the international arena of which I’ve built skills and credibility for, I’d like the opportunity to just move as a family.

That precipitated my leaving a major company and going into a large independent that needed people like me to develop activity in Egypt. I was earmarked to move with my family to Egypt and we did that. We lived as a family in Egypt for five years. It was a fantastic trip but the point was we were together doing it. I wasn’t gone all the time and I didn’t miss my kids’ plays at school and that kind of thing.

I think about it in practical terms, I’m a former military and many military families move. You pack up all your gear and go to someplace where culture is different, utilities are different, sockets are different, the whole bit. Your son was how old when you guys went to Egypt?

He was in Kindergarten.

You’ve got the mechanical side of education, the grocery store, security. I don’t know if you had security in those days or not. What was it like to get your family into Egypt? What was the challenge or thought process?

My wife and I are outgoing and we understood the detail of it going in. The company had established themselves in there a couple of years prior. I had people that used to work for Amoco who’d been in Egypt for many years, so we had a lot of lessons learned about having support for housing repair, for visas, having support on how to buy furniture in Egypt or have furniture made, things like that.

Everyone has something to offer. Sometimes you have to work hard to understand what that positive contribution is.

While I was busy freaking out about learning a whole new basin and trying to explore successfully in Egypt, my wife was busy dealing with how to get our home working, making sure my son got to school and go into the Cairo American International School. It’s a whole ball of wax and I was lucky enough to have decent briefings supported by my company. They give you a little education on working with different cultures and things like that. It was definitely an adjustment and not all families are successful. Some never adapt and go home after a year or two but we enjoyed it. We were there for five years.

How much of that do you think is attitude?

Attitude certainly helps. If I’m at work and everybody speaks English, everything’s taken care of and it is just business as usual. If the wife is not successfully integrated into the expat community, the school or the child’s not doing well in school, gets into trouble, the family’s not all working successfully then the partnership does not work to be an effective employee for the company. That’s why companies that are successful in these third world or international ventures understand that and they put a lot of effort with the HR side to accommodate people and brief them and know what to expect.

I have relatives that were in the expat community in various countries. What do you think are both the drawbacks and the positives of having your son in the international expat community?

For us, it was extremely positive. Generally, the people that you meet in international expat communities are outgoing and are successful. In Egypt for example, it wasn’t just oil and gas, it was military people. There were teachers, there was Coca-Cola, Ford and US Embassy people so you’re around a lot of positive influence. In the schools, the teachers at these international schools are with coveted jobs. They get better money and a great experience. The teachers are top notch, so it was positive for us all the way around.

Do you think that influence is going to change how your son views where he works and how he conducts himself as an adult?

Yes, he has a global view that most kids in the United States don’t have. Things have changed. The global commerce that we have and the travel, it seems to be not so exotic. Some of the places I travelled early on, people would say, “I’ve been there,” but it certainly is eight years overseas. It certainly shaped him as a person. I’ve seen a lot of my coworker’s children go on to work in international learning languages, international business, that kind of thing. He certainly has a global view that we think is useful because we are a global economy.

I did notice that some of your snow skiing adventures were in Volant Copper.

That’s right. When we were in Egypt, we luckily got three trips a year. Every year we took a week skiing in Europe, France, Italy, so we were lucky enough to see that.

Nowadays, there’s such political upheaval in challenge in parts of the Middle East. How much of that did you see early on in your career there?

In my days in Egypt, it was very stable. The US invested a lot of money there for support on USAID. Egypt and North Africa are not the center of the Middle East per se. We learned a lot about the Muslim culture being in Egypt for five years, but I never worked in Saudi Arabia for example, Iraq or Iran. I know people that did. That’s a different level of risk than Northern Egypt. Sadly, we’ve seen Arab Spring come in and cause a lot of disruption even Egypt and the whole arena part of the world.

A World of Culture, Oil and Golf: Things have changed. The global commerce that we have and the travel, it seems to be not so exotic.

A World of Culture, Oil and Golf: Things have changed. The global commerce that we have and the travel, it seems to be not so exotic.

I’m genuinely interested in both the industry, the travel and the things that you brought to the table. I was fortunate enough to be able to go through the book so that helps paint a picture. For you folks that haven’t picked the book, A World of Culture, Oil and Golf, I suggest that you do. You think about the day-to-day travails in successes and issues and the book covers that.

If you’re thinking about working internationally or thinking about traveling internationally, this is a nice resource to take a look and see what kind of things happen. I’m going to shift gears a little bit and this is the part where I ask you a whole series of questions. We periodically go off the rail, which is fun and I’m looking at some other things. In a perfect world for the book, who would you like this book to impact or serve?

As I’ve evolved and understood the people that are interested in this twenty plus years, twenty plus countries, the different business situations I experienced, and of course the cultures and yes as you point out occasionally gulf, oil and gas industry people have given me positive remarks. Military people and frequent international travelers, all could benefit from reading this book.

Most people read it and it’s a “You were there” experience. I was in Russia when they were raising the double eagle after communism fell. I was in Hong Kong before it turned back to China. Obviously, I was in Turkey before that part of it became Kurdistan. I just have the “You were there moments” that I feel like sharing and I hope people are interested to see but those are the arenas of business that I think would most definitely do reading the book.

The history of this timeframe, ever since 1980, I guess it’s like many others. There are lots of turning points, lots of upheaval and much change in some of the areas that you were doing exploration. In Kurdistan, some of the drilling techniques that they used then versus now when in Moscow are perhaps certainly not like now. You saw a lot of changes. Looking back over your career, we have our successes and failures, was there a failure or perceived failure that helped set you up for future achievement?

Instantly what comes to my mind are experiences in Egypt as a company. The business model there is a cost recovery mechanism where the government doesn’t put upfront money. The company puts up the money and the government pay its share of the operation back in future production, cost recovery.

What that means is the government approves things for cost recovery and you might have a large concession of operation where you’re spending money. If your money spending drops off, their share of production grows. We had a situation where the company made a large discovery, saw tens of different structures undrilled in that same concession. If you keep spending money that gives additional money and income of future production, they will say, “Bring six rigs out. Let’s drill all these structures.”

They drilled 22 dry holes in a row and the numbers in the oil and gas business were frightening, but even at that point those were $2 million to $3 million wells. That was a lot of money for the company. It was like, “We’re running this thing into the ground. What can we do differently?” I was fortunate enough to be on a team of good geologists and geophysicists.

We learned the source rock where the oil and gas came from, is not just across the whole area, it was in little sub basins. It was only churning for certain parts of time and in some areas. The source rock generation was done, and the oil was sloshing around, the source was shut off, so you had a geologic history to better understand.

Then we realized that we didn’t see the image very well in the structures that we were drilling, so we started shooting 3D seismic. Following that change in business practice, it took more investment and more time to figure these things out. The company went on a 50% exploration wells success rate, which for people in the oil and gas industry back in the ’80s, it was one in ten wells that we found an economic volume.

As 3D seismic evolved, in this case, there’s 50% economic success rate. That’s just not the geologists finding a bucket of oil and saying, “See? It worked.” This is economic make money for the company, the team, and the country. That was a business practice, a change that I lived through personally. Sometimes you have to decide to spend more money to be successful and reduce risk. That’s what I call reducing the below ground risk. Get more data.

If you could take and put an ad on page on one of the local papers sharing the message or advice of your book, what would it say and why?

I would say understand the host country or culture, wherever you are, engage with the people. Everyone has something to offer. Sometimes you have to work hard to understand what that positive contribution is. As a geologist, I’d say get more data.

We’ve talked a lot about where you’ve been and what you’ve done, but if you were to answer their question, what makes you an authority on this topic? What would you say to them?

In the oil and gas business I have 37 years’ experience. I’ve been a part of numerous successful campaigns and all different international or domestic explorations. I saw the onset of horizontal drilling. I’ve seen development operations and exploration turnaround. I can talk about technical details of the geology reservoir economics and also the business itself. Looking at the planning cycle, I did a lot of that.

What I typically do when I speak is I use a series of different countries that I worked in and depending on the level of interest of the audience, I may talk about the culture, what we’ve learned, and some funny stories, or I may talk about the business case that we’re in at that time. Was it a remote exploration deal or was it a development of a known field to become economic? Those kinds of things.

Looking back over time, obviously if you’re a writer, you’re a reader. What’s the most recent book or influential book that’s altered your perception on leadership or your experiences?

Following Oil: Four Decades of Cycle-Testing Experiences and What They Foretell about U.S. Energy Independence

Following Oil: Four Decades of Cycle-Testing Experiences and What They Foretell about U.S. Energy Independence

I’ve enjoyed reading The Prize by Daniel Yergin and Following Oil by Thomas Petrie. He’s at Denver. He’s a 40-plus-year investment banker. He was a leader at Bank of America Merrill Lynch. He talks about the fiscal level of advising countries on oil and gas investment and the whole global economics. That’s not necessarily my area of expertise, but I was fascinated reading that. As a child I read The Call of the Wild by Jack London. That started the adventure grains in me.

I’ve been there. I have read that too. It’s a great book. If you haven’t read it, you’re missing something for sure. When you went into some of the foreign countries and you were charged with negotiating a deal to drill in that country, what are the key things that somebody could take to the table to help them succeed in getting that done?

I was always partnered with a lawyer or a business development, somebody that negotiated full-time. I learned a lot about it and I was involved with it at times, but you have to understand the fiscal contracts of the host country or state in the United States and that’s key. In the United States, the rules are published. If you’re going into a country and you’re trying to negotiate rather than bid against numerous companies for a block of land, you want to go in and negotiate directly with the government.

Essentially, you have to understand the rules of that host country. You have to portray very clearly what’s in it for the host country and what you’re willing to spend financially. Are you going to create jobs for locals? Are you going to invest a little money and leave right away? Are you in it for the long-term? Those are the things you paint on the side while you’re negotiating a contract.

What’s in it for them?

If these countries don’t have the financial capability to run their own oil and gas company, they’re looking for outside companies to come in and they need our investment and expertise in many cases. The North Sea is a fabulous example. In the early ’60s there was gas production in the Netherlands from the giant Groningen field and they’ve discovered little gas in the North Sea, but there were no large oil fields.

Large licenses passed out because a lot of companies came in and drilled. There were about 200 wells drilled dry and people were starting to think this isn’t going to work. Then they discovered the large oil fields and it turned into a major oil and gas producing part of the world. The north seas then produced some $30 billion barrels.

The UK side got numerous fields and then the Norway side but that has been a phenomenal run. Initially, a lot of companies brought in all the expertise. When we lived in Scotland following our Egypt days, there were no more United States softball teams because most of the jobs were all handled by locals.

There were very few expats in these companies because there were plenty of bright people in the UK that learned geology roles, the drilling operations, development engineers, and production. That completely changed the work environment there. That’s a transformation into a whole industry. Before the downturn of 2014, there were some 450,000 people employed in UK in the oil and gas industry. It’s a phenomenal thing.

That’s quite a testament from basically starting at zero. Looking over your time of travelling outside the country, what’s your most unusual habit or what other folks might have thought that was unusual that helped you be effective when you traveled?

I was so interested in learning the new places that I overlooked the inconveniences and the long travel time. Keeping physically fit, and I’ve worked out all my life, that helped with jet lag and those kinds of things. I had good medical support from a lot of these companies. They made sure we had all her shots and in the early days I took Malaria medicine and that kind of thing. It’s just being prepared. In the early days I was a boy scout and I brought that with me to this international arena. Have your data, have your medicine, know where you’re going, know who the people are that you need to know, know who has the authority, know what the rules are.

Over the past few years, what belief or protocol have you established that’s most impacted your behavior in success?

Try to be a good communicator.

I’ve tried to be a good communicator. As I evolved later in my career in management roles, it was important to portray to the team, “Here are our goals. Here’s how we’re going to get there.” In independent oil and gas companies, there may be bonus potential if we’re able as a company achieve our goals. You get incentivized. If your company is looking to grow production, maybe you want to drill a whole lot of more wells, that means your people permitting wells, they’re going to double their workload, and that the land people who are in negotiating access are going to hurry up and get the permits ready and approved. It’s just a whole team environment that everybody has to work together to significantly grow your output or investment.

Talking about world market, demand and supply for oil and gas, and the oil and gas business cycle. You touched on that just a little bit right there whether you’re increasing drilling or decreasing, would you want to drive and dig into that a little bit?

That’s right. I know that during my career there were five major downturns. People were hearing in the news OPEC has decided to cut production. When we had our downturn in 2014 oil dropped into the $30 range and most oil and gas United States operations are uneconomic at that point. The Permian Basin where you can drill horizontal wells for $40 oil and make money and keep going, most of the oil and gas ventures in the United States are uneconomic at that point.

They were shutting down operations and these OPEC members understand that they need a certain level for price of oil too because a lot of them fund their whole country operation that way. It’s a real dynamic thing. The global demand for oil and gas and OPEC controlling things by cutting production or increasing production to get more flow of cash.

A phenomenal thing that’s happened with the United States in the onset of horizontal drilling was that the United States was figuring out how to extract economic volumes of oil and gas. Initially, it was horizontal drilling and fracking for gas reservoirs and then it evolved to be oil reservoirs. The technology of that is a whole world unto itself. It’s labor intensive, cost intensive but it reinvigorated many of the traditional basins of the United States. The Bạch and Dakota’s, the DJ Basin in Colorado, the Permian Basin, the Haynesville in Louisiana, and the realization that the Marcellus are phenomenal gas volumes with huge trillions of gas volumes.

The United States oil and gas production is larger now than it’s ever been since the ’50s. We’ve exceeded ten million barrels a day and going towards eleven million barrels a day. We haven’t seen that level of production in the United States for many years and the amount of imported oil and gas has dropped to below five million barrels a day which is a great way to reduce our dependence on foreign countries for our key resource in running the country.

It changes the political discussion on it because I can remember early on in the career where OPEC decided to do one thing or another. It was a swing and it was a joke point. That punctuation seems to have slowed down. Thinking about with your experience in travel, what advice would you offer to either a new CEO or a senior business leader that’s assuming that role for the first time in a foreign country?

A World of Culture, Oil and Golf: People value the words directly from the top leader; they’re like gold to some people.

A World of Culture, Oil and Golf: People value the words directly from the top leader; they’re like gold to some people.

Find some experts to talk to. There are companies that specialize in briefings for fiscal regimes of international ventures, so you look at the economics of the country itself, and then find the local people that are going to be your ears and eyes on the ground, people that are going to be dedicated to your company and be willing to tell you the truth and advise you properly. Finding those resources is probably key to being successful especially in an international arena for a new CEO.

As always, a CEO’s job is to engage his entire team the best he can. In an international arena you’re going to use some local labor. I know CEOs for larger companies don’t have the luxury of communicating that frequently to everyone, but if there’s an opportunity to do that, people value that words directly from the top leader and are like gold to some people. They motivate people and as you know, motivation for people to work hard is not just money, they want to be part of a good team. They want to create something that’s successful and valuable for others. That’s the painted picture that I see when you ask that question.

It has obviously worked for you so that’s a good thing. Thinking about misconceptions, what do you think is the biggest misconception that was either about your role as a geologist or the international experience that you had?

As a geologist, many business leaders on the engineering side or pure business leaders don’t necessarily have the subsurface understanding, they think you can punch a couple of buttons and spit out the interpreted thing and say, “Here’s a bunch of more locations.” People don’t understand the cycle time of gathering data and interpreting data. That’s one thing as a geologist I would say.

In looking back over the past few years, what would or should you have said no to and why?

When you say manage expectations, a key thing for a geologist is to describe the risk to the business decision makers, managing expectations and understanding that we had this discovery, but to expect that same ten-million-barrel discovery to happen again time after time is unrealistic because there are risks of doing that. As geologists in subsurface people, our job is to portray the risk as accurately as we can, and say when you will need more data to reduce the risk and manage expectations. It’s been a key phrase for most of my career. You want to manage expectations for the business leaders of your respective company by portraying exactly the risks involved with the subsurface.

Spend money in the right place. Try and get your return on investment.

Spend money in the right place. Try and get your return on investment. You obviously are very disciplined, or you wouldn’t have been successful traveling and writing a book. What’s that day to day self-talk or personal habit that keeps you focused? For me, it’s to enjoy what you do. It’s not just about money, it’s engaging with the people and creating something, being excited to get up in the morning and go figure out the variety of things you have to do.

Then people will say, “How are you able to write a book while you had such a demanding job that involves so much travel?” As I evolve later in my career as a leader, there are things that keep you up at night when you’re making decisions that affect people. I found time to write a book because an insomnia helps to do that. At night or on planes when everybody else has watched a movie and fallen asleep, I’m writing a little bit. Just find time. The discipline to find time to write is difficult, but I fit it in somewhere along the way.

In some of the book, I’m reading about your schedule, you’d have some periods of time where there’s a delay. I went here and I went there. Then there were times where you said, “I worked for three days in a row creating the output, getting the reports in,” and so early on in your career to be able to have an established routine would have been a luxury at a minimum.

That’s a fact. It’s a cyclical business as we talked about on a global scale and a price of commodity scale. It’s a feast or famine too. Many businesses have high periods of activity as quarter reports or whatnot, but we have that in oil and gas business too, and it may be a different driver. You have a bid deadline coming up for applying for a license in a country. You have a scheduled review for your business leaders to review everything you’re doing and what are we going to do next. Why?

They have their deadlines and quarterly reports to shareholders?

That’s right.

Through all of the times, to think about the stories, do you have a favorite scary story or a favorite funny story?

I’d have to say one funny thing was when we were in Egypt for five years and it’s a third world. It’s a desert. All the buildings are brown, and nothing seemed to work routinely. The rules were kind of ad hoc and then we moved to Scotland where everything was green. It was first world. There were plenty of infrastructure and industry. My son just said, “It’s the same. There are goats everywhere and guys wear dresses.” In Scotland, we enjoyed our time there as well. It was a beautiful place.

For the folks that want to reach out to you on social media, how do they find you?

I’m on LinkedIn, David Allard, author and retired as Chief Geologist. I have an author page, DavidAllardAuthor.com. My website has links to Amazon if you want to buy the book or if you want an autographed copy directly from me, there’s a link to do that. The website also has some of the pictures of places that we’ve talked about and descriptions of Q and A, examples of interviews for me and things about the book. I have an Amazon author page, Facebook page, author page, the usual things that most authors do.

As you’ve traveled through the years, do you have a favorite quote or one that you would draw on?

I invariably fall to, “Rome was not built in a day,” because we all get in a hurry and want to create things instantly but realize you can’t kill yourself working all night, all day forever. That’s a good one.

If I was to run across some of your colleagues and ask them what you’re best at and how do you utilize that strength on a day-to-day basis, what would you say you’re best at?

I’m personable and my communication skills are strong. I listen well. Sometimes Deborah might say I talk too much but it’s important to explain the leadership’s view of what we’re doing and the team’s view. In my team, I want them to be fully informed. Another thing, going back to another quote is a Vince Lombardi and that’s, “Perfection is not attainable but if we chase perfection, we can catch excellence.” I pride on myself on trying to be a reliable worker and produce excellent product throughout my career.

Looking at the book and yet the oil field and world stage is dynamic, what good folks tie from current events into what you’ve got in the book?

A World of Culture, Oil and Golf: I had a very enjoyable time understanding those cultures. In general, it’s a glimpse of the world cultures of which we repeatedly hear about.

A World of Culture, Oil and Golf: I had a very enjoyable time understanding those cultures. In general, it’s a glimpse of the world cultures of which we repeatedly hear about.

I look at my experiences in Russia talking about the culture there and I spent a fair bit of time in China, Thailand, the Far East. I had a very enjoyable time understanding those cultures. In general, it’s a glimpse of the world cultures of which we repeatedly hear about. There’s the Far East and there’s the West.

Russia is different and you can’t explain that until you go there. The people are very bright. They have a large country. In fact, the original Soviet Union that I grew up with has eleven-time zones. I have no idea how they managed such a vast array of countryside. It’s just mind boggling, but when I was in Moscow or in Northern Russia, Kazakhstan, which is no longer a part of Russia but its own country, just the culture is different. It’s so interesting.

Is there a favorite place internationally that you would go back to and spend time?

We always talked about going back to Guatemala. There are amazing volcanic craters. There’s jungle, there are phenomenal beaches, there are ruins from the days of the Spanish antiquities in Antigua, Guatemala City, 16th century buildings. It has it all, jungle, beaches, phenomenal architecture, a culture really interesting. That jumps out as one place and we need to go back to Egypt. I miss my friends there. We’re long overdue for a return to Egypt. We’d like to go back to the Far East as well. It’s just an amazing culture to me how people work and live there.

I think about all the years of travel and then you go from all the travel to not so much and you would have withdrawal from the itchy foot. I’ve got to believe you have an itchy foot if you traveled that much.

We’ve limited mostly to a domestic travel lately, but we talk about going back internationally when we get things sorted out with our Colorado-based business. All the international trips we made was a challenge. Moving to Denver in the fall of 2015, that is a vibrant, beautiful place, but it has become crowded. I’ve been coming to Colorado my whole life. I have family in Fort Collins area, but Denver has experienced incredible growth. Finding a house to buy, figuring things out and fighting the traffic, it was a challenge.

I’ve been here in Colorado for a very long time. I was in Denver and the traffic is incredible, which is the same everywhere in the big cities. It’s just part of the infrastructure issue. David, I can’t tell you how much I appreciate you taking time to come and share your story. For our audience out there, I would highly encourage you to pick the book up. I enjoyed it. The stories are great. The descriptions of the people, the events and the countryside are riveting. You will enjoy it.

I enjoyed talking with you, Bob. It’s a pleasure.

Thanks, David. Talk to you soon.

Links Mentioned:

- David Allard

- A World of Culture, Oil and Golf

- The Prize

- Following Oil

- The Call of the Wild

- David Allard – LinkedIn

- http://www.DavidAllardAuthor.com/

- David Allard’s Amazon author page

- David Allard’s Facebook page

- https://youtu.be/bmjLDIR2wRQ

About David Allard

David Allard began working as a geologist in the oil business in San Francisco, California after finishing school in Pennsylvania. He moved to Midland, Texas to work for a major oil and gas company in 1981 and in 1988 moved to Houston to work on international projects with that company, involving extensive travels. He joined an independent oil and gas company in 1998, moving his family to Egypt; then five years later, transferred to Scotland. David took on management roles of increasing responsibility starting in 2000 to the present. He returned to the U.S. in 2006 to work in Tulsa, OK, Houston again, then with another independent oil company to Tulsa and finally to Denver. David has had a varied career of over 35 years as a petroleum geologist, playing a part in many new field discoveries, publications and public presentations. A few of his other interests include: music, art, business management and time to help others.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join the Business Leaders Podcast Community today:

- businessleaderspodcast.com

- Business Leaders Facebook

- Business Leaders Twitter

- Business Leader LinkedIn

- Business Leaders YouTube

The post Exploring A World of Culture, Oil and Golf with David Allard appeared first on My podcast website.