From Conventional To Electric Aviation with George Bye

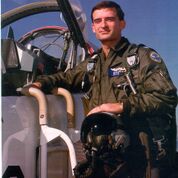

After his dad bought a Piper Cherokee 140, it became a fun family airplane over a sea-level mild-temperature family course in Corvallis, Oregon. At eight years old, George Bye was inspired watching both his parents learn to fly and became fascinated by the jets and the trip to the moon in the 1960s. He says that shaped his life and brought him to where he is today with electric airplanes. George is the founder and CEO of Bye Aerospace. He gets more intimate with us as he discusses what foreshadowed his interest in aviation, getting into the United States Air Force, flying a variety of platforms, and coming into electric aviation with Bye Aerospace.

—

From Conventional To Electric Aviation with George Bye

I was inspired at eight years old watching both my parents learn to fly and then fascinated by the jets and the trip to the moon of the 1960s. That shaped my life and brought me to where I am today with electric airplanes.

—

We’re incredibly fortunate. I have the pleasure of sitting across from George Bye of Bye Aerospace. He is the Founder and CEO and he’s bringing to market electric aviation. George, thanks for taking the time to visit.

We’re incredibly fortunate. I have the pleasure of sitting across from George Bye of Bye Aerospace. He is the Founder and CEO and he’s bringing to market electric aviation. George, thanks for taking the time to visit.

It’s sure a pleasure to be here.

Going into your comment and you said what influenced you early on. Let’s talk about the early years of inspiration when you were a kid and all of that and how it influenced you.

I would start with my mother, who is the daughter of a professor where I grew up in Corvallis in Oregon State University. She’s very creative and a great mom. She insisted that I enjoy and come to learn the arts. I played the violin starting when I was in third grade. I love sports. I played baseball. My dad and I played catch. I enjoyed very much the life of a kid growing up and all things Boy Scouts and all of that. My mom also infused in me the appreciation of the arts. She insisted that I learn to draw and paint. Of course, she herself is a professional painter. She gave me a painting and I’m deeply honored by that gift. I loved the sciences. My dad’s an engineer and that was a great influence for me. The creative side, the artistic side, the combination of both sides of the brain was brought and a part of my DNA as a young lad. I mentioned I love flying and from the get-go, I dreamed of being a jet pilot and an astronaut. All of the excitement in the 1960s about going to the moon, all of that was captured as a young person but colored very much by a mother and a father who helped shape but also allow all that creativity, science, engineering, sports to be combined together with the arts, creativity, dreaming and imagining.

I think you and I talked previously and said your mom got her private pilot’s license at first?

Back in those days, that was something. In the early to mid-1960s, women did not fly. Getting a private license first inspired the family and me as an eight-year-old in those days. Dad is next. They both became private pilots. We bought a Piper Cherokee 140, believe it or not. As a family in Corvallis, Oregon with sea level mild temperatures, that was a fun family airplane. There were two of us boys at that time. My sister came a little bit later, but we love flying and that captured me. I was hooked. I set the path for my life at that moment going forward.

Back in those days, that was something. In the early to mid-1960s, women did not fly. Getting a private license first inspired the family and me as an eight-year-old in those days. Dad is next. They both became private pilots. We bought a Piper Cherokee 140, believe it or not. As a family in Corvallis, Oregon with sea level mild temperatures, that was a fun family airplane. There were two of us boys at that time. My sister came a little bit later, but we love flying and that captured me. I was hooked. I set the path for my life at that moment going forward.

Do you remember the first time your mom gave you tutorial?

I do and it was an amazing feeling. You think two dimensionally.

How old were you when you did that?

That was all between eight, nine, ten until sixth grade, twelve years old. All of those early experiences of flying, you go from a very two-dimensional experience in life to flying as three dimensional. Going left, going right, going faster, going slower was something that was pretty easy to capture but going up and down that was like, “This is different. This is a roller coaster.” It was great fun.

I think about the perspective that changes when you’re at altitude versus the perspective you have as a kid on the ground and the influences for your mom. Your mom and dad flew, did your brother have the same joy of flying that you had?

He did and he got his private licensed later in life as well. Unlike me, I went into the Air Force, pilot, flying and so forth. My brother, David, went into the Navy. He took a different track. He still enjoyed aviation or flying as we did as a family but as a private pilot.

He did and he got his private licensed later in life as well. Unlike me, I went into the Air Force, pilot, flying and so forth. My brother, David, went into the Navy. He took a different track. He still enjoyed aviation or flying as we did as a family but as a private pilot.

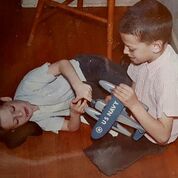

As a kid, and we all had very favorite things that we played with, was there something that you played with that foreshadowed your interest in aviation?

I remember at Christmas time, Legos were popular back then as they are now. Perhaps a resurgence in interest in Legos. I remember getting Legos. Some kids would make trucks and a house but I made an airplane. I took the wheels that were meant for a vehicle, took off the rubber and I made a little thing so that I could take some strength from the top of the stairs, ran it across over the living room, down to the fireplace mantel, tie it off and then I could fly my airplane down the string to land on the fireplace mantel. It was my first airplane design and tried it out.

Going from the single digit years that you go through, were you pretty much in the same area of the country as you grew up?

We grew up in the Northwest or Oregon and Washington State.

You went through the elementary school, high school and all that stuff and played sports. At some point, you went to university. Did you start ROTC when you first got there or was that something that came to you later?

At the time, I wanted to go back to Oregon State where dad was an alum. My father got his engineering degree at Oregon State. My grandfather was a professor at Oregon State on loan from UCLA. I was thinking, “That’s where I want to be. That’s where I want to go and do engineering like my father.” Having moved to Washington State across the river in Vancouver, across from Portland, there’s a language requirements issue. I ended up looking at the University of Washington after going to a community college there in Vancouver for the first year. I applied for ROTC in a ROTC pilot scholarship.

What year was this?

What year was this?

This is going back to 1975 and 1976.

Post-Vietnam.

After the Vietnam War, there was a tremendous draw down of the military. While I was fascinated with flying, the military was not interested in new pilots at that point. It’s very scarce in terms of pilot slot availability and then getting any scholarship for that was very remote. When I first made my application, they said, “George, this is great. It’s wonderful. I love your grades, your sports and Boy Scouts but we don’t have a slot for you. We can make you an alternate. Wouldn’t you like to be an engineer?” I said, “Thank you so much, but I want to be a pilot. I am going to stay on focus here. I’m here to be a pilot.” Back and forth, patience and over some time, six months later I got another letter in the mail that said, “George Bye, welcome to the United States Air Force. We have an ROTC pilot scholarship for you.” With great anticipation, I began my next step in life.

It came in snail mail. Do you remember when you read that?

There are moments where you can go one direction or another.

Yes, that was a huge day. There are pivot points in our life. There are moments where you can go one direction or another. That was one of those big moments in my life that shaped the next fifteen years.

The funny part about that is I got an army flight scholarship as well. When I was in, it seemed to be easy. I don’t know whether it was because I went to Tennessee and nobody flew but nonetheless. Do you remember the first day that you walked down to meet your flight instructor?

In the Air Force ROTC, you had a flight screening program. You had freshmen, sophomore and then before your junior year, there was a flight screening program, 25 flight training hours. The idea was basic airmanship skills. We’d already taken the AFOQT test, which was an aptitude test to even become or be considered to be a pilot. You had to maintain grades in the sciences and engineering, all of which were gatekeepers to a very high criteria and a very small requirement for the number of pilots at that point in our country’s history. The flight screening program was what I would call a high pucker factor. They’re not there to help you. They’re not there to give you your private license. They are there to screen you from becoming a pilot or somebody that may not have the aptitude that they were hoping for.

In the Air Force ROTC, you had a flight screening program. You had freshmen, sophomore and then before your junior year, there was a flight screening program, 25 flight training hours. The idea was basic airmanship skills. We’d already taken the AFOQT test, which was an aptitude test to even become or be considered to be a pilot. You had to maintain grades in the sciences and engineering, all of which were gatekeepers to a very high criteria and a very small requirement for the number of pilots at that point in our country’s history. The flight screening program was what I would call a high pucker factor. They’re not there to help you. They’re not there to give you your private license. They are there to screen you from becoming a pilot or somebody that may not have the aptitude that they were hoping for.

A fair amount of stress and a fair amount of focus. The civilian contractor was a very nice guy, but he had a job to do. It wasn’t like he put his arm around me and said, “We’ll slog on through this.” It was, “Here’s the deal, here’s your syllabus. There’s the airplane. Let’s get this done.” The initial training was fairly straightforward dual training but I remember vividly taxing down after what I thought was a training flight. He said, “Stop the aircraft right here.” It was next to a parking area and I was a little bit surprised. He looked over at me and he goes, “You’re a plane and got out.” My first solo, every pilot remembers his first solo. I was, “It’s on me. There’s nobody here to help out.” At that moment, you have a reckoning.

Do you remember what your downwind was like?

I do. I remember that first turn to final, everything.

I did the same thing in Murfreesboro, Tennessee and I can see it like it’s yesterday. You’re going downwind and turn base, then you go fly and you go, “I’ve got to remember all this stuff.” Then you start getting close to the runway and you go, “This is the moment.”

I’ve done it a million times since then and I can’t remember any of them but that first one, you always remember it. The first solo in the Air Force later, T-37 and the T-38 and on through my career, those moments capture you. Emergencies get your attention and are embedded in your memory and shape you. The judgments and the training, all of that is a part of your life all come together in those moments.

Do you remember where your first cross-country flight went to?

We did the cross-country flights but to your point, it’s getting out of familiar. The familiar area and going to somewhere novel new.

We did the cross-country flights but to your point, it’s getting out of familiar. The familiar area and going to somewhere novel new.

The thing that struck me about all of that as you’d have to plan and execute your plan and then you’d have to be able to follow the plan that you set up. You have to be able to go on, get signed off and come back and you go, “I didn’t kill myself along the way so that’s plus.” Then you think if you’re up there if I have a mechanical, “Where am I going to go?” I think all of those things come forward as we’re in your office with all the whiteboards, all the notes and all the effort here to bring this technology forward. I’m interested in the formative transition. You’ve finished flight program and you’re finishing ROTC.

I worked hard. I loved the Air Force. I loved even ROTC, the college days. I rose up through the ROTC ranks. I finished my senior year as a cadet colonel and the wing commander for the organization there at University of Washington, which was a real honor and responsibility. There are two wing commanders that school year split into two. It was quite an honor for the two of us. The two of us were distinguished graduates, which launched me into getting my second lieutenant and then onto pilot training. I was able to pick where I would go to pilot training. In those days, Williams Air Force base was the premium location in Phoenix, Arizona. That accelerated me in that next step of my life going from engineering school to becoming a commissioned officer. More importantly, that step into undergraduate pilot training for the air force.

You arrived in Phoenix and you’re getting ready to do your training. When you look at the advantages to having a degree in engineering versus not having, how did that affect your behavior at flight school?

It helped in terms of understanding the airplane that I was flying in particular the aerodynamics of the airplane. It set expectations as I maneuvered the plane and went through the flight envelope of the airplane. What the Air Force was looking at was a method to screen the aptitude both physically, dimensionally. The Air Force pilot aptitude requirements as well as the science and engineering mental aptitude of its pilot candidates. By using these sciences, that brought together those two features and its pilots going through training in those days like myself.

You flew a variety of platforms. What was the first jet that you flew?

I started with the Cessna T-37, twin jet primary Air Force trainer subsonic. It basically had the same performance of the classic P-51 from the World War II era. It was 300 not airplane, a little bit more but it would do all of the loops, barrel rolls and formation flying. Instruments, the traffic pattern work and all of the basic fundamentals of going from a private general aviation pilot into the introductory experience sensations and environment. The parachute and the helmet and the oxygen and all the rigors of that initial screening, the primary phase of flight training. It was meant to be tough. As few pilots as they were even bringing to undergraduate pilot training, they wanted even fewer to graduate. The attitude was not, “We’re here to train you.” The attitude was, “We’re here to screen you and reduce this class size because we have very few pilot requirements.” This is the late ‘70s, early ‘80s timeframe.

As many of us remember those days, the military was being trimmed way back Jimmy Carter days, pre-Reagan. There were very few resources and very few pilots. The few that were getting through had a few slots available. T-37 screening, I did very well. I was fortunate and worked hard. I went into T-38s, going from subsonic to supersonic. It was awesome. I loved it. I consumed this experience and again, I was very fortunate. I did very well and was able to graduate as a distinguished graduate in the top 10%. I went on into my Air Force career as a pilot with my wings and eventually able to use those skills to train others. I went to several of the various operations, wars and things that happened in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

As many of us remember those days, the military was being trimmed way back Jimmy Carter days, pre-Reagan. There were very few resources and very few pilots. The few that were getting through had a few slots available. T-37 screening, I did very well. I was fortunate and worked hard. I went into T-38s, going from subsonic to supersonic. It was awesome. I loved it. I consumed this experience and again, I was very fortunate. I did very well and was able to graduate as a distinguished graduate in the top 10%. I went on into my Air Force career as a pilot with my wings and eventually able to use those skills to train others. I went to several of the various operations, wars and things that happened in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

We were talking to this a little bit before as an instructor pilot. You’ve got your skill sets that you’ve learned, broadened and honed and then you start bringing in the students. What I was interested in is how much of the lessons on the airframe you brought forward, to what you’re doing at Bye Aerospace from watching what it did do and watching mistakes from the student pilots and so on.

I look back and look forward, the experience, the technical piece, the airmanship, the judgment required as an Air Force pilot, particularly in my Euro-Nato Joint Jet Pilot Training days. Flying the T-38 as an instructor training new NATO fighter pilots or student pilots who were to become fighter pilots was a combination of undergraduate pilot training and introduction to fighter fundamentals. UPT and IFF are very unique fighter program. Again, starting in 1983 to 1988, I was there training these students from NATO. At the end, I was a pilot instructor trainer. In other words, I trained the new instructors. As a part of that, there’s a tenacity and grit. The ability to manage stress that is simply a requirement in the three-dimensional chess game of being a fighter pilot. You’ve got the physical experience. You have to manage your aircraft and a threat that would very much like to kill you.

It’s a serious game. It absolutely captures everything, all of your entire capabilities, physical and mental is finely tuned in this. The key thing is you’ve got to know your limitations. You go right up to the edge but not beyond. Understanding yourself and the other people that you’re working with on your side as well as your enemy, is the part of what I carry forward as an entrepreneur, as a business person. In a cutting-edge development of a new technology and a new company both again, working with our team and the expectations of the team as well as understanding the potential threat, the competition, if you will that’s out there or we’ll be out there. It’s very much a life experience for me from my military days that shaped and formed who I am now with business.

As you look back over all of your military flight experience, my father was a fighter pilot and so there are stories. Is there a favorite story or memory that you have as a pilot in the Air Force?

There were many of the operations that I went to and by that, I mean wars. There were skirmishes, El Salvador and Peru where there was a context of combatants. There was Panama, which was a relatively short engagement. The regime change that was underway there. Then Desert Shield and Desert Storm, which was a full-on battle to end all battles. At the time, the front page of the major magazines, Time magazine and etc. It was the crescendo of the Reagan era leading into what’s dominating our worldview. What we allow with this worldview with the Berlin Wall coming down but still these large reminisce of the Cold War. Saddam Hussein controlling the vast amounts of oil as well as the Kuwait invasion and so forth.

That was the backdrop of going on a mission with my crew in the C-141. I remember vividly, very late at night flying in with a load of bombs, rockets and bullets in the C-141. C-141 is a four-engine transport built by Lockheed Martin. It’s a marvelous airplane about the same size as a Boeing 707. If you can picture a 707 maybe only it was a high wing cargo plane by Lockheed Martin. It did a marvelous job transporting troops and cargo into the various areas that we had to resupply. In those days, making preparation and ultimately the engagement of the war. I flew in there one night into Saudi Arabia. The war was fierce. It was underway. The air war had just started.

Where did you depart from?

Where did you depart from?

I forward deployed to Spain and flew out of the Madrid area. The redeployment of the supplies coming from the States or from depots in Europe, we then would forward deploy into Saudi Arabia to be launched into Iraq. It was five and a half to six and a half hours going in and an hour, two or three on the ground and then turn back around. I would generally have a twelve or thirteen-hour day, sometimes eighteen or twenty. My longest day was 36 hours, which is sometimes what you have.

I think about focus and attention as you’re flying a dangerous load. You get on the ground, you want to get unloaded, you want to get out of there and get the plane back in the air. I think about the various waves of focus, relax, focus and relax. Did you find that conditioned you for what you’re doing?

When you’re at war in that circumstance, it was very serious business. Our airplane was full of explosives. I wasn’t carrying Crayons and Legos. I wasn’t carrying furniture or electronics. I wasn’t carrying people, although sometimes I did carry soldiers. I was carrying bombs for the bombers and fighters to carry on into Iraq. You definitely have a pucker factor. There is a level of background stress. Nothing can go wrong. My team and my crew are paying attention to every detail because our lives depend on it. The team that we’re giving these bombs to, the weapons to, their lives depend on it too. Ultimately, we’re looking at and we care about the soldiers that are on the ground. Talk about intensity, there’s no doubt about it.

Imagine the possibility of what the future might look like.

I’m flying into this space in Saudi Arabia, literally as I taxi then we open it up the back doors, the armament teams come right up to the back door and immediately start unloading these 500-pound bombs. They are going right onto the British fighters one by one and they’re going right literally into battle. Within a matter of few minutes, it was a rhythm of as soon as they’re unloaded, they’re going right to the airplanes. I went into command post to get my exchange orders as they were doing this. Dark night, the glow of the lights on the tarmac and the base sirens go off. Wail of screaming sirens, loudspeakers, “Map five condition red.” It means we expect that you are the target and we expect that the target load on the way to get you is either nuclear, chemical or biological.

What that meant was an immediate response put on your poopy suits, helmets, scrub each other, you go into a team. A team check thing, you check each other out, you put on these rubber poopy suits, you hit the wall in the bunker and two Scuds are on the way and our air base was the target. You have about two minutes between that notice and the expectation of the missiles hitting. It’s an interesting time to know that you’re targeted, to know the weapons are like very bad weapons, not just explosives, but that contain things that are very bad and say your prayers. You reckon your life right there, “What am I doing here? Does this matter? Has my life mattered?” I checked my buddy well and he’s checked me out one more time. The impact was a little bit long. The all-safe siren went off. Unfortunately, some people were not so fortunate. The missiles did impact and cost casualties, but we were told to immediately evacuate. All of the procedures and protocols were immediately dismissed. It was literally, “Race to your airplane. Get it off the air base as fast as you physically can. No lights, no flight planning, no nothing. Get the airplane off the air base now.” It’s quite a story, I’ll tell you.

I think about the adrenaline push. You run like hell, get your plane up in here and at some point, you’re past the danger area presumably then I think about the adrenaline crash and you’re still supposed to land the plane.

As a reminder, normally you refuel and you have a flight plan, you know where you’re going and etc. We had none of those things. Nothing was loaded, it was literally crisis, “Get the airplane airborne as fast as possible.” There were F-15s flying across in front of us, a tanker went right over across above us. It was to get out of dodge as fast as you can.

You transitioned from fighters to a C-141. I’m familiar with the inside and the back door of a C-141, I jumped out of it. That’s my familiarity. It’s a nice plane and noisy when you jump. How did you transition from fighters to C-141s?

Following my service at Sheppard Air Force Base, there were opportunities for various fighter jobs or airplane jobs. My family wanted to return to Washington State to where we grew up and so forth. My kids were growing up and my wife and I wanted to return to Washington State. We looked for opportunities there and C-141s out of McCord had a job opening. I applied and began my time there almost immediately with these various operations.

There’s that moment where you separate from service and you go into the civilian world. What was that like for you?

It was very difficult because I loved the Air Force. I truly did, everything about it. It energized me. In that period of time and for America, there were things that mattered that we were involved with that we’re trying to make better. All of that training, the judgment, working with my teams, my crew, airplanes and things was all fully realized. All that potential was put to action. The transition right there at the end was disappointing with the Somalia. It’s tragic in so many ways. It’s not a high point for sure. In transitioning into civilian life, there’s an immediate need and I enjoyed very much working as a civilian contractor for military development of airplanes.

It was satisfying but not in the same way that the military experience had been for the majority of the time from ROTC into T-38, C-141s. That was equally important too because as I transitioned into contract work as an employee of FlightSafety under a contract for Raytheon to develop the new T-6, especially towards the end of the 1990s. I learned a great deal about the real world of business contracting, government and military acquisitions and both in a good way as well a deeply frustrating way. I love to tell a story. The T-6 is a turbo prop trainer that in those days was under development for the Air Force and the Navy. We had equally disappointing results for both services.

They have a different mission and they have a different way of operating their airplanes. Both Air Force and Navy were frustrated and as part of the team to try to deliver to them a quality product, what I found was very frustrating in the bureaucracy, the acquisition and development process and the engineering process was always compromised. Rather than this ideal scenario in the Air Force where I was training to an optimum result, what I found in government contracts and development was every time there was a compromise that was made. That was inspiring. That was what transitioned me into entrepreneurship and in my own business.

Somewhere in there, the Javelin showed up. Talk about the transition into developing the Javelin.

Somewhere in there, the Javelin showed up. Talk about the transition into developing the Javelin.

My thought was there has got to be a better way. We can’t have seventeen people determining paint color, it’s not that hard to do. When we look at what the mission is, what a design against that mission and the elements of design that make that up, I imagined there was a better way. In my experience, I was a fighter, instructor-trainer and taught Aerodynamics. I was the Aerodynamics course prime. I taught Aerodynamics to the students in T-38s and later to the instructors as well. That was what we called Applied Aerodynamics. That was aerodynamics with a purpose.

I imagine as an entrepreneur and as a business person going from FlightSafety and Raytheon into the development of the Javelin, that there was a design with a purpose. The characteristics of the airplane where theoretically or technically interesting. They were purposeful in having an outcome. That was what the Javelin was. The Javelin in every way was a modernized T-38. Like the T-6 program, it was to be certified under the Part 23 FAA’s requirements. There was an opportunity for civilians to use it as well as the military. Really fine and great people. We were able to invite industry leadership to join us in the journey and an amazing outcome with the Javelin.

I think about a T-38 civilian version. You think about it now, it seems like there would be a fair amount of desire for that type of platform. As you look back at the Javelin process and coming into Bye Aerospace, what do you think the chief benefit to Bye Aerospace that you brought forward from the Javelin experience?

The continuity was a design with a purpose. There were technology advances in the early 2000s through 2007 that we captured composite structures, advanced turbo fans, advanced aerodynamics and the ability to analyze aerodynamics, not just in a wind tunnel but also with a digital analysis out of CAD. We called Computational Fluid Dynamic Analysis. Computers starting to come to play going from analog displays to digital displays and using GPS. We were capturing all of these new technologies into the Javelin with great interest in the market from individuals. The sports car of the sky, as well as militaries wanting performance and economy using civil-based aerodynamics and aero structures and things rather than the aerospace and defense approach, which is multi times more expensive. It was lots of fun and great experience. Very shaping in terms of going forward with Bye Aerospace. All of those same elements are true in capturing the benefits of electric technology structures, aerodynamics that the digital transition out of the previous analog approach. Together with that, the new regulatory background, the FAR Part 23 FAA Certification Process has also transitioned to a much more modern approach. All of those shaping now Bye Aerospace.

Everybody has moments. There was a moment where you said, “I’m going to pick a different power plan,” where you decided that electric technology in an aircraft was something you were going to pursue. Take us to that moment and what you were thinking.

I’ll go back to my roots. The Piper Cherokee 140 in the mid-1960s, that same airplane is flying now. The Cessna 172 that I got my own private license on in the 1970s is still flying. The internal combustion engine and the aviation gasoline that it consumes is still in use now. In the mid-2005, 2006 timeframe, I was very fortunate to have a red-carpet tour of the very emergent, Tesla warehouse and their R&D center. They had a couple of Roadsters back in those days that were prototypes. I was fortunate to be able to be a passenger and I was given a demo. Everybody was skeptical about electric. Everybody was dismissive except for imagine the possibility of what the future might look like. Take those technology trends and imagine where they’re going. When the driver stepped on the accelerator of that little Roadster, I was forced back in my seat just like I was in the full afterburner in T-38 a few years ago.

I’m going, “This is anything but boxy, slow and sluggish. This is amazing.” My mindset went from, what does the future look like with one set of technologies to add another technology into that mix of emerging technologies. The key was the electric propulsion system, not batteries but motors and the powered electronics that go with them. The toolset added the special feature with applied aerodynamics or applied technology, we began to imagine the possibility of this great general aviation industry that was a part of my life from the very beginning. Now, it’s almost obsolete. The current generation of airplanes are 50 years old. Applying these new technologies around the benefits of electric was the launch point then for Bye Aerospace. Specifically, not just the performance of electric but the operating cost benefit of electric. The cost of electricity as an energy source is multiple times less than aviation fuel. About $3 per flight hour compared to about $50 per flight hour for the aviation gasoline. Disruptively affordable, not a continuous line or lineage of evolution but a breakpoint so significant we would say disruptive

I’m going, “This is anything but boxy, slow and sluggish. This is amazing.” My mindset went from, what does the future look like with one set of technologies to add another technology into that mix of emerging technologies. The key was the electric propulsion system, not batteries but motors and the powered electronics that go with them. The toolset added the special feature with applied aerodynamics or applied technology, we began to imagine the possibility of this great general aviation industry that was a part of my life from the very beginning. Now, it’s almost obsolete. The current generation of airplanes are 50 years old. Applying these new technologies around the benefits of electric was the launch point then for Bye Aerospace. Specifically, not just the performance of electric but the operating cost benefit of electric. The cost of electricity as an energy source is multiple times less than aviation fuel. About $3 per flight hour compared to about $50 per flight hour for the aviation gasoline. Disruptively affordable, not a continuous line or lineage of evolution but a breakpoint so significant we would say disruptive

As you were talking, I’m thinking about the Tesla and then you look at the flight platform and you have to imagine the curve of technology improvement to get a viable product. At that time, I’m thinking about how do you take and extrapolate a vision when the technology is not keeping up with your vision. Then as importantly is how do you take and talk to your investors to help share that vision?

It’s tough. Back to that tenacity, grit and courage scenario of the Air Force days, you have to have persistence and staying power. I could imagine the future but that was ten years ago. Imagine back ten years ago with me, nobody shared that vision. There weren’t people going, “Electric aviation, of course.” I would give a speech and people would be polite for the most part. There’s always somebody in the audience, “George, how long is your extension cord?” and everybody would laugh. They’re not laughing anymore.

Looking back over your career and life, visualization’s a big part of an artist. I think in the 3D flight world, you have to visualize where you are and where the other plane is. I think about that ability to extrapolate, how far away do you think the Sun Flyer is from what you were envisioning ten years ago? Is it pretty close or a big difference?

What we do, who we are, and the legacy that we leave matters.

What we have is a Cessna 172 that is very similar to what I learned to fly on back in the 1970s. The eFlyer with the electric motor instead of the conventional motor. We put an electric motor on a 172 in the early days just to begin the process of research and development. We went to a prototype of this airplane next to demonstrate what the propulsion system and performance might be. Going from this prototype, eventually we’ll be going to production. The nose of the airplane is very different. It’s very sleek and very low drag compared to boxy and heavy. The propulsion efficiency is much better on the eFlyer because more of the propellers exposed to provide thrust as compared to the big square nose on a Cessna.

You also had material advances.

The composite air frame is half the weight of the aluminum air frame on the Cessna. There is twice as much aerodynamic drag on the Cessna as compared to the e-flyer. Aerodynamics, structures, electronics and inside is the secret sauce with the electric motor and batteries. A three-and-a-half-hour flight time carrying 450-pound payload, the Cessna 172 with full fuel equivalent, 433 pounds of payload over 130 knot airspeed compared to about 129 knot airspeed. In every way electric, much like the Roadster is performance as well as economy compared to the legacy aircraft that we’re replacing.

I remember the first time I drove an electric car. It’s all on or all off. I was herky-jerky going down the road because you’d try to take and get consistent on your power delivery. On the aircraft, it’s all power. What’s the durability difference on the electric power plant versus the old Cessna 172? There’s an extraordinary difference between moving parts.

I remember the first time I drove an electric car. It’s all on or all off. I was herky-jerky going down the road because you’d try to take and get consistent on your power delivery. On the aircraft, it’s all power. What’s the durability difference on the electric power plant versus the old Cessna 172? There’s an extraordinary difference between moving parts.

The Cessna manufacturer’s name is Lycoming for the internal combustion engine. A wonderful legacy engine going back 50 years, literally 160 horsepower, 946 moving parts and need to be maintained and essential to flight. You want to make sure that it’s maintained very precisely and that becomes a very expensive undertaking. In electric motor, we use a Siemens Electric Motor and it has one moving part. It’s 98%, 97% efficient in converting energy into torque and thrust. An internal combustion engine, 23%, 25%, 26% efficient in turning fuel into torque into thrust. The bottom line behind an electric motor isn’t just efficiency but it’s an incredibly robust design by definition. If you think about it, grandma’s old fan from 1933 in the attic of your garage maybe or something still works.

I think about locomotives, they’re powered electrically and ships. You have the vision, now you in the process of getting approval to take it to market. That’s government hoops you have to hop through. You’re thinking 2020 maybe?

Probably early 2021, the FAA Certification Process is very rigorous, which is wonderful and we want it to be safe. The bottom line for them and for us is a safe product. In this case with the eFlyer, this two-seat eFlyer that we’re starting with, this mission is training. All of new pilots like I was back in the ‘60s and ‘70s or like you were, all of us will experience a high tech, very efficient aircraft with the eFlyer but the number one criterion for you and for me is that it’s safe to fly.

I think about the trainer market. I can’t imagine what the maintenance costs are to run a fleet of aircraft. You remember in the Air Force, how many of your plans are up, how many of the players are not up but how many have been cannibalized for parts? When you talk to the various schools about what you’re bringing to market, what are their chief concerns and for the folks that are advocates of your platform, what are they saying?

The two things are operating cost and maintenance cost. They are trying to maintain a fleet of 50-year-old airplanes. It’s not just the fuel that carries them aloft for a student training sortie, it’s the time in the garage. It’s the time in the shop to keep that motor going that’s 50 years old. Imagine the parking lot full of cars that are 50 years old and you’re driving them four, five, six times a day. The happiest person on the planet is going to be, the dozens and dozens of maintenance guys staying busy perhaps to try to keep all of those cars on the road.

What about the 50, 60-year airframe fatigue?

Fatigue is a major issue. The fleet literally is nearing obsolescence.

Fatigue is a major issue. The fleet literally is nearing obsolescence.

What was the plan timeframe for the airframe to be serviceable until catastrophic failure?

The fleet of airplanes as ancient as they are required by FAA regulation to have a 100-hour inspection and an annual inspection. The complete overhaul of the engine, depending on the engine but every 1,500 hours or so. Happily, while it’s very expensive to maintain the fleet, they’re inspected very regularly so that, while it may be old and shaky or something, but they do attempt to keep a very safe aircraft as old as they are.

As contrast to the Siemens Electric Motor, that technology’s been around for how long?

One hundred years-plus.

In contrast, assuming FAA rules are the same for the power plants, is there much maintenance you have to do to an electrical motor?

There isn’t. There’s one moving part to inspect, the bearings. It’s a very simple five-minute inspection. The amount of costs against the 100-hour review, the annual review and the overhaul is extremely minimal. There are just connections, electronics and the one moving part. Operating costs is extremely low at about $3 per flight hour but so is the maintenance costs. In combination, the overall operating of the airplane is about maybe $20 per flight hour as compared to $110 per flight hour for a Cessna 172. $110 versus $20, that’s a game-changer. That changes everything.

Given the current battery technology, what’s the recharge time?

It’s not much different than the amount of time needed to refuel with a fuel tank. Refueling is about twenty minutes or thereabouts. You call the fuel truck to come out and they refuel and close everything up. The same type of an approach with a supercharger on the electric airplane as you taxi in, you turn the airplane over to the maintenance guy, he comes out with a battery truck or a supercharger and the airplane is plugged in for ten or twenty minutes between flights. The next instructor and student come out about the same operating rhythm as a normal flight school and you’re on your way again.

It’s not much different than the amount of time needed to refuel with a fuel tank. Refueling is about twenty minutes or thereabouts. You call the fuel truck to come out and they refuel and close everything up. The same type of an approach with a supercharger on the electric airplane as you taxi in, you turn the airplane over to the maintenance guy, he comes out with a battery truck or a supercharger and the airplane is plugged in for ten or twenty minutes between flights. The next instructor and student come out about the same operating rhythm as a normal flight school and you’re on your way again.

I think about if I’m the flight school operator, how many planes do I have to have 80% or 90% of them flyable?

That’s a great point because the number of airplanes being 50 years old means the number in maintenance at any given time is much higher than a new fleet.

You’ve got to have a bigger fleet to keep operational. As you see this coming to market for the folks that are going, “I want to know more, I want to get in line,” or whatever it is, what’s the best way for them to reach out to you?

ByeAerospace.com and in the website you can see the program, the details about performance, its characteristics, price and things. There’s also a link or info to make inquiry, ask questions and engage in a potential process if you might be interested in an airplane.

I think about your flight vision since a kid to now and you have 4,000-plus hours military flight time. From this point, I’m sure you’re looking out eight, ten, X number of years. What do you see for electric aviation?

This transition from conventional to electric is underway. I believe the recognition is beginning to take hold. I see going from two seat to four seat and then on from a single engine approach to a twin. It’s harder to go faster and it’s more expensive but drag costs you a lot in terms of energy. Drag is expensive in terms of the amount of energy required to overcome drag. As the technology matures, the opportunity for larger and faster airplanes becomes realized. Starting with the trainer is an ideal performance and technical entry point.

Starting as a trainer is where there’s such a critical need aligned with the requirement for new pilots that the airlines are demanding in the months, years and even decades ahead. A great opportunity from a business, from a technology and from an airplane. As these pilots grow in their experience, a four-seat airplane with an IFR capability, the twin engine airplane that’s heavier and faster becomes realized as the technology continues to advance. I see over many years, the maturing of the market, the integration of more electric into our experience as a culture, as an industry and specifically as general aviation.

If somebody says, “Why George Bye? Why is George still pushing on the aviation advance?” What would you say to them?

What we do, who we are, the legacy that we leave matters. For me, my life and my experience has been in aviation back from my formative years. That’s where I exist. That’s where my life is. My upbringing and my faith all reflect on I want to leave the world a little bit better place. Grandma taught me, my dad taught me, my mom taught me, clean up your room but not to maintain it. Leave it a little bit better than when you were there. My heart, my desire with our industry is to try to leave it a little bit better place. I’m inspiring my team and when I give talks and things, I try to talk about not just the new technical opportunity but leaving the world a little bit better place with a great airplane, a great technology and a very clean and green outcome with that electric propulsion system.

The thing that I see an observation is for the aviators and the potential aviators that can’t afford the cost of a flight education, given the current price and technology, this could revolutionize the opportunity for the pilot to go and get certified that’s actually cost-effective.

Applied aerodynamics is aerodynamics with a purpose.

Thank you for mentioning that because that is so critical. Right now, 80% of student pilots drop out because of cost and this approach with the electric propulsion system and that much lower cost means an opportunity has opened up for a much broader audience to experience flight perhaps as a private pilot. More importantly from the professional perspective, perhaps as a career, as an airline pilot. The opportunity, the gateway is that initial experience, that initial training, becoming a private pilot, the expense and experience of that with electric will be very positive and clearly much less expensive.

I can’t tell you how much I appreciate you taking time and sharing your journey. I thank you very much.

Thank you so much.

Important Links:

About George Bye

Aviation executive and entrepreneur. I strive to innovate and pioneer new approaches and technologies. Spotting market opportunities, designing and developing concepts, executing with vision and passion are among my talents. I think creatively and propose novel technology, or the synergy of new technologies that combine into extraordinary performance and value. I am an active proponent of the aviation industry. I attempt to articulate a compelling vision, persuading people to embrace and work hard to realize the potential benefits of a revitalized aviation industry for us and future generations.

Aviation executive and entrepreneur. I strive to innovate and pioneer new approaches and technologies. Spotting market opportunities, designing and developing concepts, executing with vision and passion are among my talents. I think creatively and propose novel technology, or the synergy of new technologies that combine into extraordinary performance and value. I am an active proponent of the aviation industry. I attempt to articulate a compelling vision, persuading people to embrace and work hard to realize the potential benefits of a revitalized aviation industry for us and future generations.

Love the show? Subscribe, rate, review, and share!

Join the Business Leaders Podcast Community today:

- businessleaderspodcast.com

- Business Leaders Facebook

- Business Leaders Twitter

- Business Leader LinkedIn

- Business Leaders YouTube

The post From Conventional To Electric Aviation with George Bye appeared first on My podcast website.